How the Who Changed Rock Forever With ‘Tommy’

Pete Townshend has always been obsessed with stories, not just songs. In the mid-’60s, there were few songwriters (the Kinks’ Ray Davies comes to mind) who were more interested than the Who guitarist in crafting songs that related a short tale or painted a character portrait.

Listen to those early Who singles and album cuts: Many of them are simple, two-and-half-minute stories – "A Legal Matter," "Pictures of Lily", "Tattoo" and (most importantly) "I’m a Boy."

When the idea of a “rock opera” was just a glimmer in Pete’s eye, he had the idea of a larger musical piece called Quads that was set in a future when parents could select the genders of their children. The main conflict of the story (and the one at the heart of "I’m a Boy") is that one couple gets a boy instead of the girl they ordered, but make do the best they can with the unwelcome child.

The bigger project was never completed – and may not have been really attempted – but it did result in a great slice of power pop for the Who and a No. 2 U.K. hit in 1966. Townshend continued to think about musical stories that could expand beyond a quick-hit radio single.

When extra material was needed for his band’s sophomore LP in 1966, he wrote the six-part, nine-minute "A Quick One, While He’s Away" – the most significant precursor to the album-length story of Tommy. A year later, the Who released arguably the decade’s best concept album: The Who Sell Out didn’t link songs by subject matter, but by the idea of a pirate radio broadcast complete with goofy fake ads.

Listen to the Who's 'A Quick One, While He's Away'

Townshend’s ambitions continued to grow as the Who were creating a larger global presence for themselves with the American breakthrough of "I Can See for Miles" and the band’s electrifying performance at the Monterey International Pop Festival. The rock opera Tommy followed on May 23, 1969.

By then, full-length studio projects were becoming more important than the single in rock 'n' roll, thanks to parallel successes from bands like the Beatles, and the Beach Boys. Townshend wanted to do something to fully capitalize on the album as a continuous art form – even more so than Sell Out. He also wanted to reach new audiences who had not been particularly interested in the Who’s blasts of "Maximum R&B," and felt people would be interested in a longer musical piece.

Townshend endeavored to address themes of spirituality in pop music. As someone who had recently become a follower of the teachings of Indian spiritual leader Meher Baba, Townshend was looking for an outlet to explore what he was learning. He felt that rock fans would be out to find the same answers he was seeking. Tommy would be dedicated to Baba, who died months before the album’s release.

Townshend has joked that, in the run-up to Tommy, he would talk about the notion of a rock opera to anyone who would listen. That included Rolling Stone magazine founder Jann Wenner, who spoke with the guitarist at length in the summer of 1968 about the Who’s next project.

"The package I hope is going to be called Deaf, Dumb and Blind Boy, Townshend said. "It's a story about a kid that's born deaf, dumb and blind and what happens to him throughout his life. The deaf, dumb and blind boy is played by the Who, the musical entity. ... But what it's really all about is the fact that because the boy is 'D, D & B,' he's seeing things basically as vibrations which we translate as music. That's really what we want to do: create this feeling that when you listen to the music you can actually become aware of the boy, and aware of what he is all about, because we are creating him as we play."

Listen to the Who's 'Sensation'

As Townshend explored his newfound spirituality and toured extensively with the Who, he began to piece together bits of the Tommy story. "Sensation" was based on a sexual attraction he had to a fellow Baba follower in Australia. "Sally Simpson" came from an ugly experience on the road. Other songs came from deeply personal places in Townshend’s memory.

He farmed out a couple of songs to bassist John Entwistle, both of which involved the violent and sexual abuse of the album’s protagonist. Townshend later said that he had been abused as a boy. Because he didn’t want to deal with this aspect of his past at the time, he subconsciously left those tunes for John to write, who penned "Cousin Kevin" and "Fiddle About" in a darkly humorous manner.

As the Who began recording Tommy in late-’68, the story came together. A boy who witnessed a tragic death as a child goes catatonic and becomes deaf, dumb and blind. We hear about his trials and tribulations growing up, before Tommy becomes cured with the smashing of his image in a mirror. He turns into a messianic celebrity who is adored by hordes of followers until he starts to preach about simple living. They reject Tommy, who recedes back into his inner world.

Feeling that he had captured most of what was happening in his head, Townshend played a rough version of the album for critic Nik Cohn, who was not as impressed with the scope of Tommy. The two discussed Cohn’s reaction and concluded that the serious tragedies of the story could be lightened by the presence of a breezier tune.

Knowing that Cohn was a pinball buff, Pete suggested that Tommy could be a mystical master of pinball. Townshend hastily wrote "Pinball Wizard" and the Who recorded it in the winter of 1969. They slapped it in the middle of side three and Cohn now called Tommy “a masterpiece.”

Listen to the Who's 'Pinball Wizard'

Other critics were similarly taken with Tommy, lavishing praise on the double-LP as a breakthrough for the Who and as one of the most daring albums in rock 'n' roll. The project introduced the band to a new level of superstardom, as "Pinball Wizard" became a hit single and the Who hit the road for marathon performances of (most of) Tommy along with other live staples.

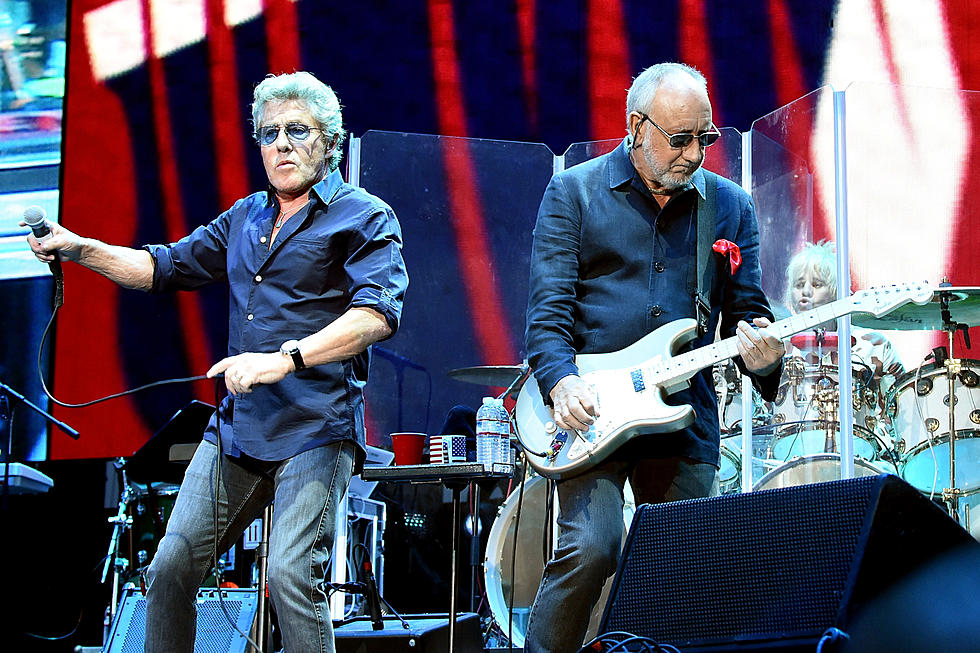

As the lead singer, Roger Daltrey became Tommy for the audience – especially in the band’s widely seen, and heavily fringed, Woodstock appearance. Daltrey discovered a new, more powerful voice in the Tommy performances on Live at the Isle of Wight or Live at Leeds. He stopped trying to sing like the high-voiced Townshend and found a lower, fuller sound that became his calling card.

Of course, the Tommy story doesn’t end there. In 1972 there was an all-star orchestral recording and, in 1975, it became a surrealistic movie directed by Ken Russell and starring Daltrey, the rest of the Who, Tina Turner, Eric Clapton and Elton John. All-star casts were assembled for Who reunion performances in 1989 in New York and Los Angeles. The Who’s Tommy became a full-blown, Tony Award-winning Broadway musical in 1993.

Through it all, the original album remained a cornerstone of rock culture as music’s most famous rock opera. It’s also one of the Who’s most commercially successful albums, having sold more than 20 million copies. If Tommy’s reputation has since been downgraded from “masterpiece” (because of Pete’s pretensions or some silly plot-connector songs), it’s partially because Townshend topped himself in 1973 with the Who’s more substantial Quadrophenia. One rock opera is never enough.

Rock Hall's Worst Band Member Snubs

Why Don't More People Love This Album by the Who?

More From WWMJ Ellsworth Maine